Published on March 04, 2021 by Polina Mikhaylova

Cities and companies globally are facing ever-tightening budgets due to the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing a serious rethink about how they operate and provide services.

Public transit agencies also now need to factor social distancing into their day-to-day operations, cutting capacity on buses and trains and reducing potential customers. But cities also don’t want people getting into their cars and creating more pollution. So, what’s the middle ground?

Transport experts have increasingly focused on options that can enable social distancing, are cheap, and environmentally friendly. This can be seen in the huge amount of walking/cycling initiatives that have popped up globally since the onset of the pandemic – from Paris adding 650 kilometres of new bike lanes to London’s streetscape initiatives where pavements have been widened for pedestrians. While walking and cycling can plug some gaps, sometimes people just need speed and ease to get where they’re going, and e-scooters fit that niche perfectly.

Mixed, proactive mobility modes that encourage social distancing have been key over the past year, where the individual takes charge of their own journey. Micromobility modes like e-scooters have been instrumental in this surge, and even prompted the UK government to speed up legislation to introduce e-scooter trials across the country. The benefits and potential pitfalls are clear, but what of the costs?

Docking vs. dock-based economics

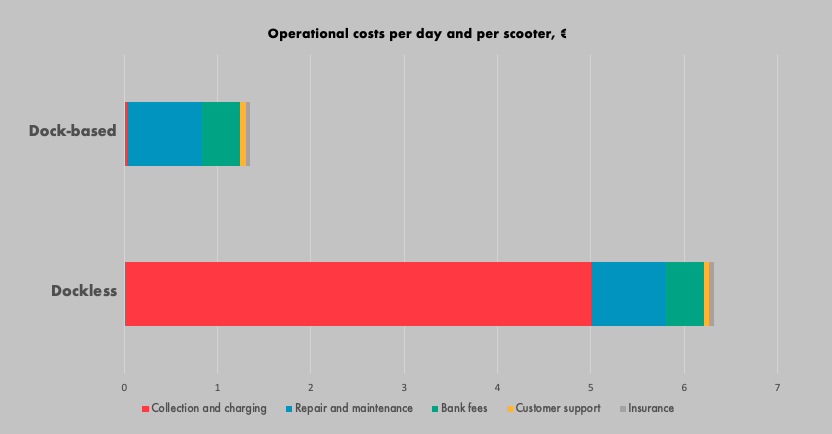

Docking stations reduce operational costs – scooters are locked and charged at the station – meaning there is no need to employ staff to collect scooters every night to swap batteries. The cost breakdown compared is impressive, operational expenses per scooter goes down from almost 7 € to 1 € per day.

On average it costs €0.03 to charge one docked scooter, versus €2-6 for free-floating scooters, when all other operational costs are factored in, and the average docking station’s lifespan is 5 years.

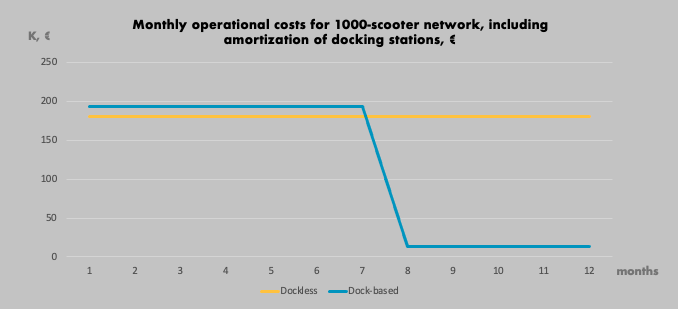

Naturally, dock-based solutions require a substantial investment into infrastructure. For 1000 scooter network cities would need to install around 250 docking stations with 8 slots each, which represents around 1,4 M € including scooter upgrade.

The bigger picture

Taking the time to look at the bigger picture can save cities a lot of trouble and money – in just seven months the initial cost of a docking-based system starts to pay off when compared to a free-floating model. This investment is not just financially astute, it also creates infrastructure that can lead to a more secure transit ecosystem where e-scooters can be viewed not as nuisance or novelty but an integral part of the transit network.

Make it flexible

But as every city is different, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach. For example, in Strasbourg, KNOT allows users to park two metres around the actual station if it’s full (the City of Strasbourg is against free floating e-scooters and doesn’t allow it anywhere else in the city).

At KNOT’s new projected network in the Gold Coast, Australia, users will be allowed to pause their trips for 30 minutes in free-floating mode, before bringing the scooter back to the station.

Having flexible options that suit users’ needs gives cities a real opportunity to make the e-scooter a mode of transport that can be truly embraced.

As more countries and cities across the world look to e-scooters as a solution (most recently Ireland, which this month confirmed they will change legislation to introduce them) those responsible for their rollout need to consider how they can impact the change in their mobility ecosystem.

Docking offers a wise investment and the chance to cement this micromobility mode into the urban landscape.